Did Border Controls Help?

The Covid-19 pandemic led to a massive return of the nation state. National governments around the world took far-reaching measures to control the spread of the disease, whether just closing shops, restaurants, and schools, or a complete and total lock-down of public life. In Europe, the crisis was, and still is, a fundamental challenge to European Union principles, notably solidarity, policy coordination, and free movement across national borders. In this paper, BCCP Doctoral Student Kalle Kappner and his co-authors Matthias Eckardt and Nikolaus Wolf focus on the temporal reintroduction of national border controls within the Schengen area. While such restrictions clearly involve costs, the benefits are disputed.

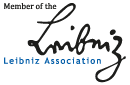

Their main finding is that the temporal reintroduction of border controls within the Schengen area helped contain the spread of Covid-19. The authors use a new set of daily data of confirmed Covid-19 cases at the level of 213 European regions, compiled from the respective statistical agencies of 18 Western European countries. Their data runs from calendar week 10 (starting March 2, 2020) to calendar week 17 (ending April 26, 2020). Figure 1 shows developments over time.

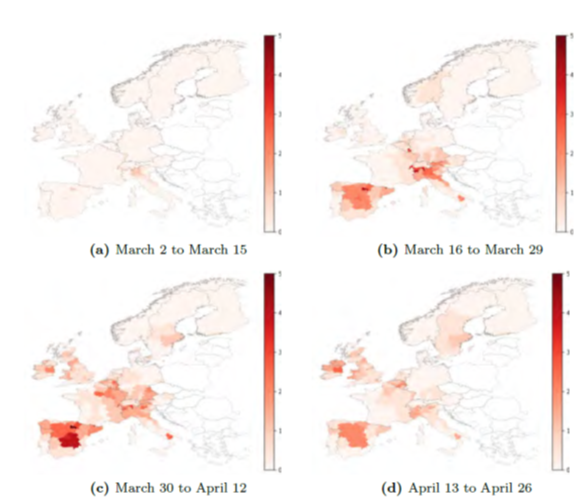

With this data, the authors test for treatment effects of border controls on new Covid-19 cases. They do this in two steps. Controlling for regional specificities and country-wide variation in containment policies (based on an econometric model with region and country-time fixed effects), they show that border controls are associated with a 25% reduction in daily cases. Importantly, they show that border controls mattered only for regions with a substantial number of cross-border commuters prior to the crisis, which is missed in the existing literature. Figure 2 shows the number of daily new cases in treatment and control regions over time, conditional on day and region fixed effects (panel a) and the estimated excess risk in treated over control regions (panel b). Apparently, the introduction of controls helped to reduce the excess risk.

In a second step, the authors show that it is important to consider unobserved spatio-temporal heterogeneity. This is likely to matter for at least two reasons. First, local containment policies might have differed from nation-wide measures and their information on such local measures is incomplete. Without such data, they might overestimate the effect of border controls. Second, the fixed effect regression approach is likely to miss some of the spatial dynamics in the data, as described by Tobler’s First Law of Geography: "Everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things." To deal with this, the authors use a Bayesian INLA approach. With this they model the idea that Covid-19 cases in one region will be affected by cases in neighboring regions. Moreover, they use this to control for unobserved variation across regions using spatial random effects. With this more flexible approach, they find smaller, but still significant, effects of border controls of about 6 %.

The authors conclude that the temporal introduction of border controls was certainly costly but made a measurable contribution to containing Covid-19. At the same time, it is likely that better policy coordination at the European level could have generated these benefits with lower economic (and political) costs; for example, if based on European economic clusters with a closer monitoring of cross-border commuting flows. Instead of closing national borders, a European agency could coordinate local containment policies in affected regions on both sides of an affected cluster.

The full paper “Covid-19 across European regions: The role of border controls” is available as CEPR Discussion Paper 15178 and is published in Covid Economics.

This text is jointly published by BCCP News and BSE Insights.